The Supreme Court of India (SC) has reserved its judgment in a case challenging the constitutionality of the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004.

WHY IN NEWS..??

The Supreme Court of India (SC) has reserved its judgment in a case challenging the constitutionality of the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004. The outcome of this case is expected to have far-reaching implications for the future of religious education in India, as it touches upon important issues such as secularism, the right to education, and the balance between religious and modern education

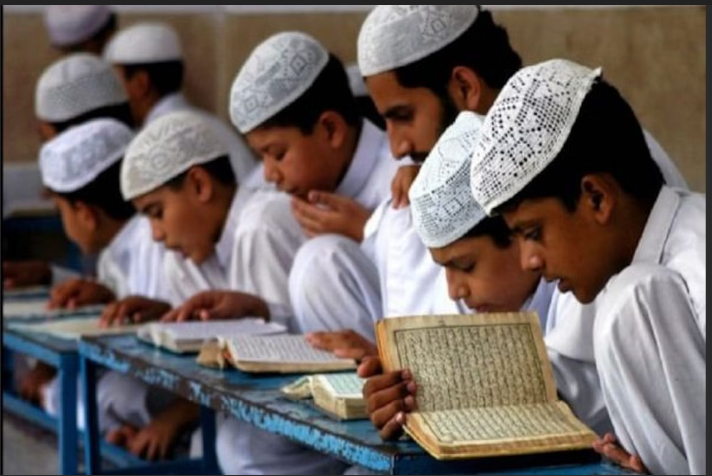

STATUS OF MADARSA

The Uttar Pradesh Madarsa Education Act, 2004 regulates the functioning of Madarsas—educational institutions that combine religious teachings with certain modern, secular subjects, with a primary focus on religious instruction.

The Act established the UP Board of Madarsa Education, which is predominantly made up of members from the Muslim community. This board is responsible for formulating the curriculum and administering examinations for different madarsa courses, ranging from the ‘Maulvi’ level (equivalent to Class 10) to the ‘Fazil’ level (comparable to a Master’s degree).

Key Grounds on Which Allahabad HC Declared the Madarsa Act Unconstitutional:

- Violation of Secularism:

The court referred to past Supreme Court rulings to stress that secularism requires equal treatment of all religions by the state. The court pointed out that the Madarsa curriculum made Islamic religious education mandatory while offering modern subjects as optional. This was seen as conflicting with the state’s duty to provide secular education.

It also emphasized that the government should not favor any particular religion or sect through its education policies. - Violation of the Right to Education:

The High Court ruled that the Madarsa Act violated Article 21A of the Indian Constitution, which mandates free and compulsory education for children aged six to fourteen.

The court argued that the madarsa curriculum failed to meet the quality standards set by the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009, and criticised the state for not ensuring comprehensive education for madarsa students in modern subjects. - Conflict with the UGC Act:

The court found that the Madarsa Act conflicted with the University Grants Commission (UGC) Act, 1956. The UGC Act gives only recognised universities the power to award degrees. Since the Madarsa Board was granting degrees, it was deemed unconstitutional as it overstepped UGC’s authority.

Key Arguments on Constitutionality of the Madarsa Education Act in the Supreme Court:

- Religious Education vs. Religious Instruction:

A central issue was whether madarsas provide “religious education” or “religious instruction.” The distinction is important because Article 28 of the Constitution prohibits religious instruction in state-funded institutions but allows religious education that fosters communal harmony.

The madarsa board’s legal counsel argued that the High Court wrongly conflated the two, leading to the conclusion that the Act violated secular principles. - Striking Down the Entire Act:

Another debate was whether the High Court should have struck down the entire Act or only the specific unconstitutional provisions. Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud noted that the state has the authority to regulate madarsa education in line with secular values without abolishing the entire Act.

Wider Implications of the Supreme Court’s Decision:

- The verdict will likely have a national impact, influencing not just madarsas in UP but other religious educational institutions like gurukuls and convent schools that integrate religious teachings.

- The case raises broader issues about balancing religious education with secularism and the state’s role in ensuring all children, regardless of religious background, receive a modern education.

- Chief Justice Chandrachud stressed that while regulating religious instruction, secularism must be appropriately considered.

Conclusion:

The Supreme Court’s upcoming decision could set a critical precedent for religious education in India, potentially reshaping how religious and secular education coexist in the country’s diverse educational framework.

Q1: What is Secularism as per the Indian Constitution?

Secularism, introduced in India through the 42nd Amendment in 1976, means keeping religion and politics separate. The government does not endorse or follow any particular religion but treats all religions equally.

Q2: What is the significance of Article 28 of the Indian Constitution?

Article 28 ensures the freedom of religion in educational institutions and guarantees a secular educational environment by prohibiting religious instruction in state-funded schools.